Andrew Lacey

Managing Principal

In the recent case of In the matter of Gondon Five Pty Limited and Cui Family Asset Management Pty Limited [2019] NSWSC 469, the New South Wales Supreme Court (Brereton J) considered the purpose and scope of an appointment as receiver to a company, and came down particularly hard on an insolvency practitioner for performing work and incurring expenses which were determined to be outside, or not incidental to, the scope of his appointment.

On 2 December 2016, the applicant Dominic Calabretta (“the Receiver”) was appointed, on the motion of the plaintiff Tracy Cui (“Tracy”), to be interim receiver and manager of the respondent companies Cui Family Asset Management Pty Ltd (“CFAM”) as trustee for the Cui Family Trust (of which Tracy was a beneficiary), and Gondon Five Pty Limited (“Gondon”). In its trustee capacity, CFAM was the sole shareholder in Gondon, which was undertaking a property development.

On 13 September 2016, Tracy obtained freezing orders against CFAM and Gondon (“the Companies”). The Receiver was appointed on 2 December 2016 because it appeared that the freezing orders had been ineffective to prevent adverse dealings with the Companies’ assets. The Receiver was appointed until 21 December 2016 and directions made with a view to an interlocutory hearing on that day to determine whether the appointment would continue thereafter.

The Companies became concerned at the extent of the work which the Receiver, his staff and solicitors appeared to be undertaking, and challenged his approach. Accordingly, at the Receiver’s request, the proceedings were re-listed on 15 December 2016. On that day the Court confirmed that “the purpose (of the Receiver’s appointment) was to take custody of and secure the assets and undertaking of the corporations in question and prevent there being any further dealing with them until the interlocutory hearing”. The Court also confirmed that there was no need for the Receiver to prepare a formal report.

On 21 December 2016, the Court was informed that the substantive proceedings had been resolved. Two days later orders were made, by consent, that the Receiver be discharged. The Receiver had been in office no longer than 21 days or 14 business days.

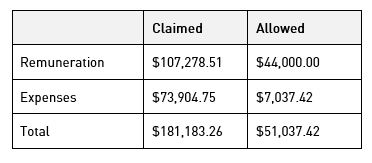

The Receiver applied to the Court for orders fixing his remuneration as receiver at $107,278.51 (incl. GST), and approving payment of his expenses (being the legal costs of his solicitors, Piper Alderman) in the sum of $73,904.75 (incl. GST). The Receiver also sought orders authorising him to draw such remuneration and expenses from funds of the respondent companies.

Rule 26.4 of the Uniform Civil Procedure Rules 2005 (NSW) states that a receiver is to be allowed such remuneration (if any) as may be fixed by the Court. Brereton J summarised the relevant principles at [34]. They included that a receiver is entitled to the costs, charges and expenses properly incurred in the discharge of the receiver’s ordinary duties, or in the performance of extraordinary services that have been sanctioned by the Court. Further, in fixing remuneration, the ultimate question is what amount of remuneration is ‘reasonable’.

Brereton J stated at [54] as follows:

By far the most significant issue in this case concerns the scope of the Receiver’s appointment: to what extent was the work in respect of which remuneration is claimed reasonably undertaken in the due course of the receivership. … This issue turns on the nature of the Receiver’s appointment, and the scope of work that was reasonable to achieve its purpose.

Brereton J went on to note that it was plain from the orders that the Receiver was appointed as an interim receiver and manager, with it being plain at all times that whether his appointment would continue beyond 21 December was contested and was to be resolved at an interlocutory hearing on that date.

Brereton J also observed that although a receiver has all the powers referred to in s 420 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), which are listed (a) to (w) in s 420(2), that “does not mean that it was necessarily reasonable or appropriate to invoke them, especially in the context of an interim appointment”. Further, “the function of a receiver and manager remains essentially to preserve the status quo … This all the more so in the case of an interim appointment” (at [58]-[59]).

Brereton J proceeded to analyse the evidence adduced by the Receiver establish that his remuneration and expenses were fair and reasonable.

The evidence included a letter from the Receiver’s solicitor to the respondents’ solicitor which stated: “The receiver sees himself as an independent and non-partisan representative of the court, appointed by the Court to secure the companies’ property, investigate the companies’ affairs and, and report back to the Court”. Brereton J observed that it was therefore plain from the Receiver’s own evidence that he had misconstrued his task because:

Unlike a liquidator, a court-appointed receiver – especially an interim one – is (at least absent specific direction) neither required nor expected actively to identify the property to be collected and received, nor … to conduct investigations. (at [64])

Rather, as Brereton J confirmed at [68], “[t]he Receiver’s function was merely to take possession and control of the assets of the companies, so that they could not be dissipated and would be preserved pending the interlocutory hearing”.

Brereton J also held that the Receiver had erred, and was not justified in causing the matter to be relisted for the purpose of seeking directions (in relation to the purpose and scope of his appointment) without making any prior approach to any party to make the application. In this regard, Brereton J confirmed the appropriate procedure as follows:

It is (typically) the plaintiff who obtains an order for appointment of a receiver and the initial description of the receiver’s function and powers; and if the receiver is in doubt, then the appropriate course is to approach the plaintiff and ask it to make any necessary application for clarification. Except perhaps in cases of urgency, it is only appropriate for the receiver to make the application if the plaintiff refuses or fails to do so. (at [86])

Brereton J was also critical of the scope of work which had been carried out by the Receiver’s solicitors in the matter. His Honour commented at [98] that “where receivers are required, within the scope of their appointment, to undertake steps about which legal advice would ordinarily be obtained – such as the sale of real property – they would act reasonably in retaining solicitors for that purpose”. However, they “should not engage solicitors to advise generally on matters relating to the conduct of the receivership”. After assessing the work done by Piper Alderman pursuant to their retainer His Honour concluded that the Receiver was not justified in retaining solicitors other than in connection with the lodgement of a caveat and its withdrawal, and the exchange of contracts in respect of two units (which should not have involved a great deal of work), and in particular, he was not justified in instructing them to attend court on the various hearings of the substantive application, nor to make and attend on the application for directions.

The ultimate result of his Honour analysing the remuneration and expenses claimed and applying the relevant principles, including those referred to above, was as follows: