Foez Dewan

Principal

The Federal Government has progressed a number of legislative initiatives that will impact on directors and are likely to come into effect in 2019 if they go ahead. The proposed new laws include significantly increasing civil and criminal penalties for breaches of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), introducing a new Director Identification Number regime and making directors personally liable for the unpaid GST debts of their companies.

Proposed new legislation will see some changes for directors that are likely to happen in 2019 if the legislation is introduced and passed. These include:

So, what do these proposed changes mean for directors?

The introduction of the Penalties Bill is a clear response to the Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry (Royal Commission), with a significant change to penalties.

The Commonwealth Treasury warns that the Penalties Bill “… would double maximum imprisonment penalties for some of the most serious ‘white-collar’ criminal offences bringing Australia’s penalties in closer alignment with leading international jurisdictions”.2

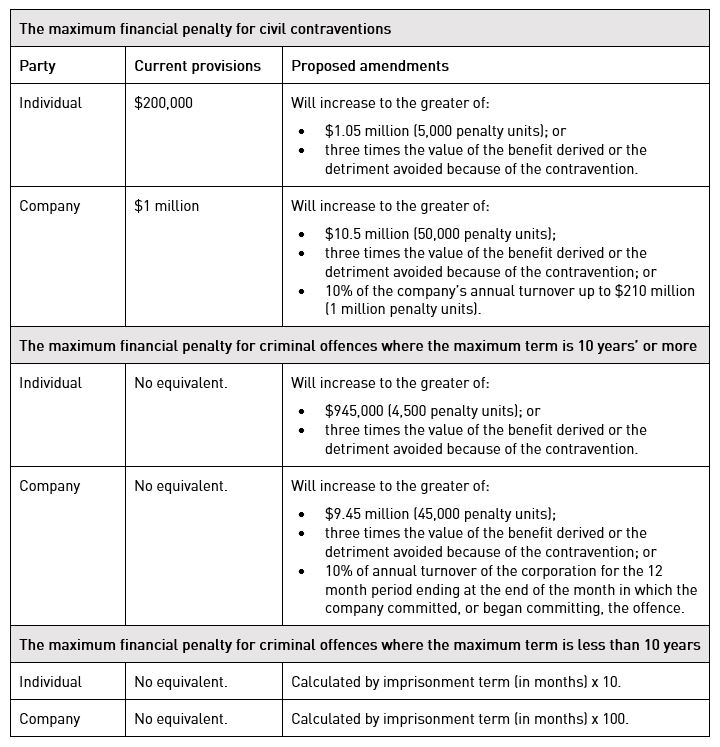

The Penalties Bill proposes to significantly increase the civil and criminal penalties for breaches of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) from the current penalties, as summarised below, and also introduces new formulae to calculate the maximum penalties for civil and criminal contraventions as summarised below:

(1) A director or other officer of a corporation commits an offence if they:

(1) A director or other officer of a corporation commits an offence if they:

(a) are reckless; or

(b) are intentionally dishonest;

and fail to exercise their powers and discharge their duties:

(c) in good faith in the best interests of the corporation; or

(d) for a proper purpose.

The amendment will erase the requirement to prove the director (and other officers) intentionally acted dishonestly and failed to discharge his/her duties in acting in the best interests of the corporation.

The impact of the proposed changes and the introduction of an objective test for dishonesty is that directors who consider their conduct as honest or may not have intended or known that their conduct was dishonest may still be found to have contravened the Corporations Act such as liability under subsections 184(2) and 184(3) for dishonest use of position or information, and section 588G for dishonestly trading while insolvent.

Under the draft Legislative Package,3 it is proposed to introduce a requirement that each registered director applies for and obtains a unique Director Identification Number (DIN) under a newly inserted Part 9.1A of the Corporations Act and Part 6-7A of the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (Cth).

In addition to the DIN requirement, the draft Legislative Package proposes to consolidate Australia’s thirty-five business registries administered by ASIC and the Australian Business Registry (ABR) (New Register). Operating alongside the DIN requirement, both changes should improve the traceability of directors’ relationships between entities and to better track illegal phoenix activities.

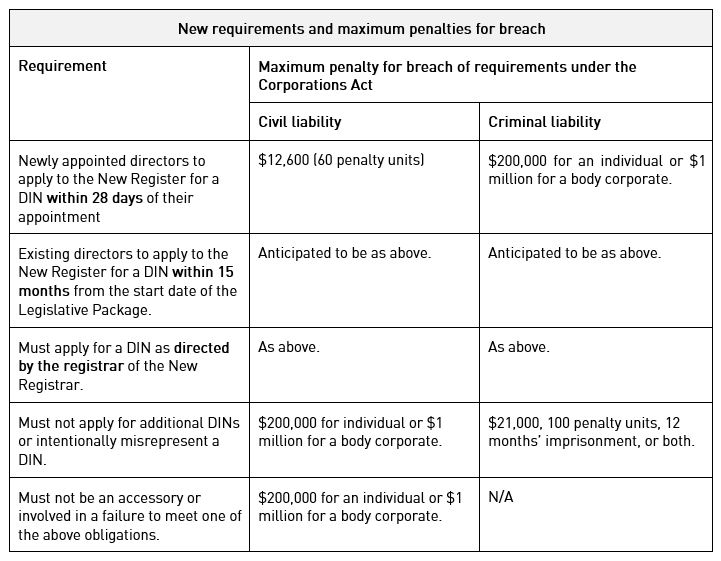

The following table summarises the proposed new obligations directors will have in respect of DINs and the maximum penalties for breaches of those obligations:

2 Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia, ‘Government consults on stronger penalties for corporate and financial sector misconduct’ (Joint Media Release, 26 September 2018) 3.

2 Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia, ‘Government consults on stronger penalties for corporate and financial sector misconduct’ (Joint Media Release, 26 September 2018) 3.

3 The Treasury Laws Amendment (Registries Modernisation and Other Measures) Bill 2018 proposes to amend the Corporations Act and the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006.

4 Set out in Division 269 in Schedule 1 of the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (Taxation Administration Act).