McCabes News

In an effort to stem the spread of COVID-19, the Australian and state governments have implemented a number of restrictions on the operations of Australian businesses. In these challenging times, it is important for both businesses and individuals to be aware of their rights and responsibilities in relation to the provision of goods and services, including with respect to cancellations and refunds.

The ACCC has established a special taskforce to address consumer complaints and ensure that businesses are complying with their obligations to provide refunds or other relief to consumers due to cancellations or suspension of services.

The Taskforce is dealing with a large number of complaints and enquiries from both consumers and businesses and has adopted an early intervention strategy to resolve issues now, rather than taking enforcement action down the track.

The relationship between businesses and their consumers is governed by the terms of any contract between them, as well as the provisions of the Australian Consumer Law (ACL).

Businesses and consumers must continue to comply with the terms of their contracts, subject to the operation of:

Irrespective of the terms of any consumer contract, the ACL protects consumers by establishing their fundamental rights and entitlements, which cannot be abrogated by contract. Of particular relevance during this time, the ACL provides for consumer guarantees, which are rules that automatically apply to all goods and services purchased by consumers in Australia. There are different consumer guarantees for goods and services.

The ACL establishes a number of obligations on businesses, including:

The ACL defines “consumer” to mean a person (including a business) who:

In this article, we provide an overview of the consumer guarantees under the ACL and explain how the ACL applies to topical issues facing businesses and consumers in the midst of COVID-19.

There are a number of guarantees that businesses need to comply with in relation to the provision of goods in Australia, including:

The manufacturer of the goods is also required to comply with some of these guarantees.

In those instances, if there has been non-compliance with the guarantee, the consumer has the choice of pursuing a remedy from either the supplier business or the manufacturer.

All of these guarantees also apply to second-hand goods and goods purchased online. Some of them apply to goods purchased at auction.

However, these guarantees will generally not apply to goods purchased from overseas sellers or one-off purchases from private sellers.

Businesses need to comply with the following consumer guarantees in relation to the provision of services in Australia:

However, these guarantees do not apply to contracts of insurance, contracts for financial services, or contracts for the transportation or storage of goods for commercial purposes.

If a business has breached any of the consumer guarantees, the consumer may be entitled to a remedy.

The type of remedy that the consumer is entitled to will depend on how egregious the noncompliance with the guarantee was.

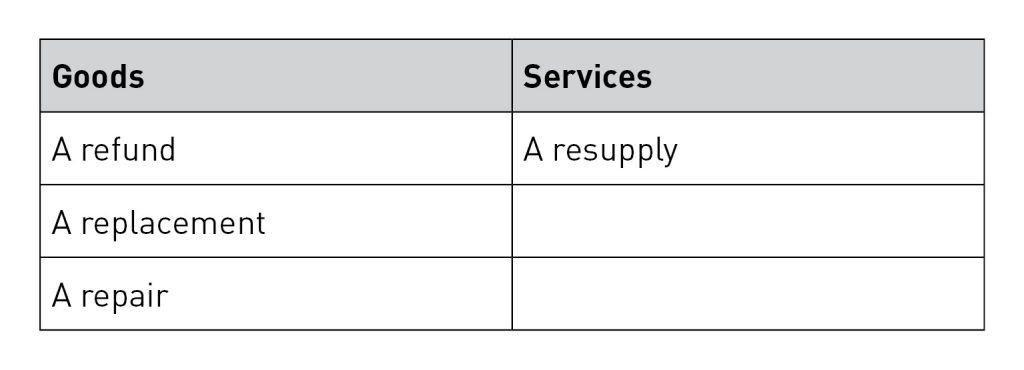

If the breach is minor and can be resolved in a reasonable period of time, the seller can choose to offer one of the following remedies:

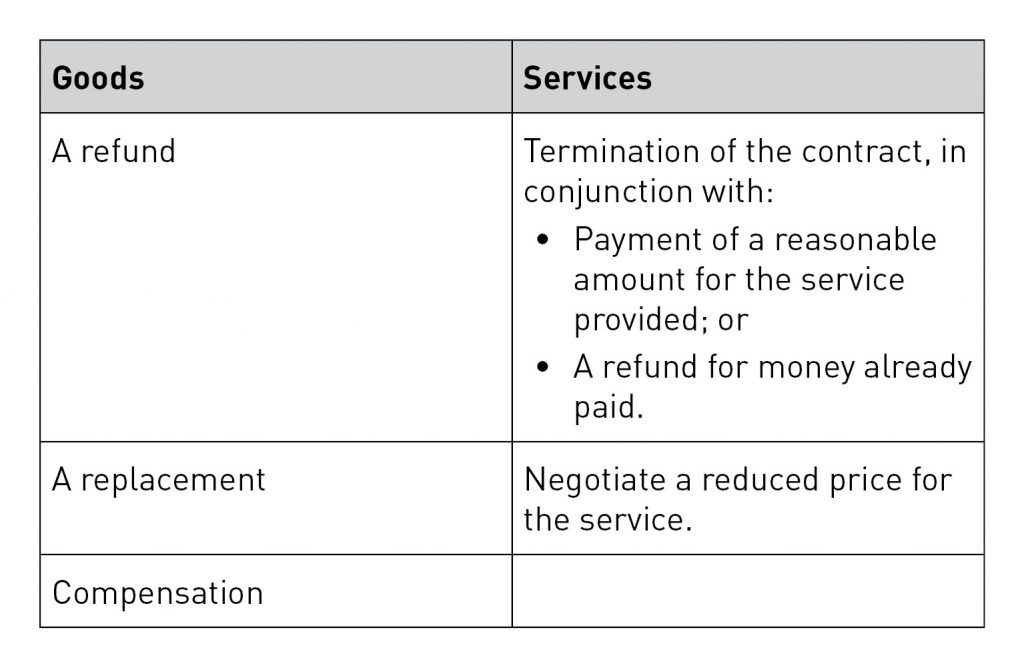

If the breach is major, the consumer is entitled to choose one of the following remedies:

In the current climate, consumers may understandably have a preference for receiving a full refund from a business that is unable to provide the goods or services in question. However, both consumers and businesses should be mindful that consumers are not automatically entitled to a full refund in these circumstances.

If travel plans, functions or events have been cancelled due to government restrictions, the ACCC has advised that it is unlikely that consumers will be entitled to a refund pursuant to the consumer guarantees under the ACL.

However, consumers may be entitled to certain remedies in accordance with the terms of their contract, which includes the terms and conditions of event tickets. Businesses are not permitted to retrospectively change any terms and conditions to alter the contractual rights of consumers at the time the contract was entered into (or when the ticket was purchased).

Furthermore, consumers may be entitled to other remedies at common law.

Gyms and providers of subscription services are not entitled to continue charge fees when there are reasonable grounds to believe that the services will not be supplied (unless the consumer consents). This is the case irrespective of whether the contract allows payments to be suspended. Consumers who have had fees deducted during periods when those services could not be supplied are entitled to be refunded.

Consumers may also have rights under the terms and conditions of their contracts.

In order to comply with government restrictions, gyms and subscription service providers may offer alternative services during the closure period (for example, online classes). Where these alternatives constitute material changes to the services that the business was contracted to provide, consumers will generally be entitled to cancel the contract.

If a business is unable to deliver goods to consumers as a result of supply chain issues, the consumers will generally be entitled to a full refund from the business.

However, if the business never received the goods from its supplier, the business may be entitled to be reimbursed by the supplier in accordance with the terms of their contract.

Generally, pricing of goods and services is set by the market and businesses are free to set prices as appropriate based on supply and demand.

However, in some circumstances, excessive pricing (or ‘price gouging’) can constitute unconscionable conduct under the ACL.

Furthermore, businesses may be liable for misleading and deceptive conduct under the ACL if they make false or misleading representations about the reason for the price increases.

Finally, as of 31 March 2020, it is an offence under the Biosecurity Act 2015 (Cth) to sell prescribed essential goods (including, disposable facemasks, disposable gloves, alcohol wipes, and hand sanitiser) for more than 120% of the price that the goods were purchased for. This only applies if the goods were purchased after 30 January 2020. The Australian Federal Police have enforcement powers in relation to the offence provisions. The relevant provisions will be in force until at least 18 June 2020 but may be extended as long as COVID-19 remains a biosecurity emergency.

Given disruptions to supply chains and international trade, businesses may be required to source their supplies from other sources and countries.

In those cases, businesses should update the labels on their products to accurately reflect the manufacturing process and supply chain of their products. Failure to do so could constitute misleading and deceptive conduct under the ACL.

The ACL and consumer guarantees apply the same now as ever – COVID-19 has not changed their operation.

However, in these unprecedented and trying times, businesses should be more conscious than ever to make sure that they are complying with the ACL and if unsure – should seek legal advice.

McCabes has experience in advising its clients and resolving disputes in relation to the Competition and Consumer Act and the Australian Consumer Law, as well as advising its clients in relation to their contracts including unfair contract terms. Get in touch today.