Andrew Lacey

Managing Principal

Unpaid internships are often viewed as a rite of passage for those entering the workforce. But any business looking to engage an intern must ensure that it does so in accordance with the law. This three-part article series explains the relevant law (Part 1), outlines how to set up a proper intern arrangement (Part 2) and highlights the importance of getting the arrangement right (Part 3).

In this article, Part 1 in our series on internships, we examine the relevant law to help you understand the legal requirements for an internship.

Unpaid internships can offer those without relevant experience an opportunity to get their foot in the door in some of the workforce’s most competitive industries. However, businesses need to be aware that unpaid internships are only legitimate when undertaken as part of a vocational placement related to the individual’s course of study or in circumstances where an employment relationship does not exist.

The primary purpose of an internship is for the individual to learn, observe and develop skills. As the Fair Work Ombudsman, Sandra Parker has said “Business operators cannot avoid paying lawful entitlements to their employees simply by labelling them as interns. Australia’s workplace laws are clear – if people are performing productive work for a company, they are legally entitled to be paid minimum award rates”.1

Businesses need to understand the distinction between legitimate unpaid internships, which offer genuine work experience, and sham internships that exploit cheap (or free) labour, to ensure they do not fall foul of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (FW Act).

To be properly categorised as an unpaid intern, an individual must:

The FW Act expressly excludes individuals on a vocational placement from being considered an employee.

A ‘vocational placement’ is a placement that:

If a placement does not meet each of these requirements, it is not a vocational placement for the purposes of the FW Act and the individual may, depending on the facts and circumstances of the arrangement, be entitled to receive wages and other employment entitlements.

As outlined above, a vocational placement must be undertaken as a requirement of an education or training course. This generally requires an arrangement between:

The course must be authorised, such as a university award course or for an accredited course offered by a registered training organisation.

The placement does not have to be a prerequisite for the student’s overall course of study or even be assessable in order to satisfy the vocational placement exemption. Rather, the internship must simply be a placement that is a requirement of the course, unit or subject.

Example: Vocational placement/unpaid internship

As part of her university accounting degree, Elizabeth is awarded course credits for undertaking a placement within a host accounting business.

Because the placement is considered part of the university course, it satisfies the requirements of a vocational placement. Elizabeth is not an employee of the host business and is not entitled to receive wages or other employment entitlements.

Example: Not vocational placement

Following completion of his university graphic arts degree, Simon begins to perform work as an ‘unpaid intern’ at a local magazine.

Because Simon has already completed his degree, his work at the magazine is not part of a vocational placement. Depending on matters such as the tasks that Simon is requested to perform, he may be considered an employee of the magazine and be entitled to wages and other employment entitlements (see further example below).

As mentioned above, the primary purpose of an internship is for the individual to learn, observe and develop skills. As such, the benefit of an unpaid internship should predominantly flow to the individual rather than to the productivity of the business.

An individual is likely to be considered an employee if they are expected to perform work ordinarily carried out by an employee, as opposed to altruistically offering their services as a true ‘volunteer’. Bearing this in mind, some circumstances that might indicate an employment relationship are as follows:

A good question for a business to ask itself is this – Are we expecting the intern to complete productive work? If the answer to this question is ‘yes’, it is likely that the individual would be considered an employee.

In addition, the longer an arrangement lasts and the more regular the hours of attendance, the more likely the arrangement will constitute an employment relationship.

Example: Unpaid intern

James is studying radio journalism and in order to gain further insight into the industry he attends his local radio station for 3 hours each week for a month. James does not do any tasks that would otherwise be performed by an employee.

Because James merely observes the radio station operations and shadows the station’s employees, he is enjoying the main benefit from the arrangement and no employment arrangement exists.

Example: Employment

Following completion of her university marketing degree, Kate begins to perform work as an ‘unpaid intern’ with an online retail business. Kate creates content for the website and accompanying social media accounts, for 2 days each week.

Even though Kate may have agreed not to receive payment for the work she performs for the online retail business, she does work that would have ordinarily been performed by a paid employee. This indicates the existence of an employment relationship and Kate should receive wages and other employment entitlements.

Businesses should not pay wages to true interns. While minor reimbursements for things such as travel expenses or lunch are permitted, any remuneration that is calculated based on hours worked will be characterised as ‘wages’ and exclude the individual from the FW Act’s definition of ‘vocational placement’.

If they are being paid for the work being performed, the individual is likely to be rendered an employee for the purposes of the FW Act. In those circumstances the individual will be entitled to remuneration and other employee entitlements regardless of the individual’s title. This also means that the remuneration should be at an appropriate level and pay scale for the individual’s position.

The act of taking on an unpaid intern who does not meet the statutory requirements (even if done innocently) is likely to expose a business (and in some cases individuals) to liability for breaches of the FW Act (see Part 3 of this series). As we outline above, simply calling an individual an ‘intern’ is not enough. The title ‘intern’ does not legitimise underpayment of salary and entitlements.

Before looking to engage an unpaid intern, a business should carefully consider whether the internship arrangement:

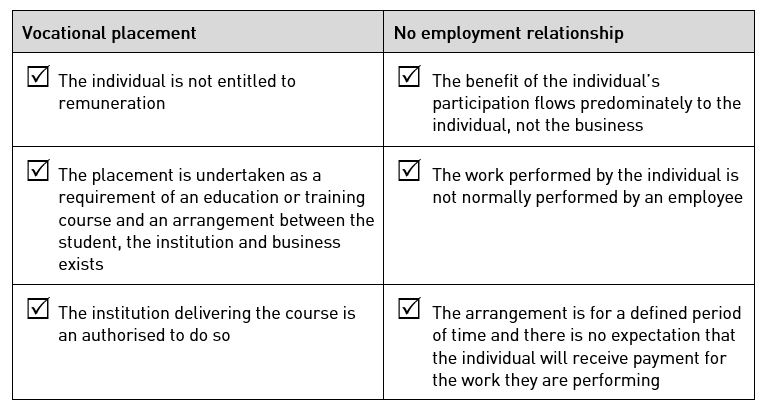

Although each arrangement needs to be considered on its own merits, here is a quick checklist of the matters usually considered when determining whether an individual can be engaged as an unpaid intern because they are either undertaking a vocational placement and/or there is no employment relationship.

Part 2 of this series, we outline some guidelines for setting up an unpaid intern arrangement that aims to mitigate the risks that can arise when engaging an unpaid intern. In Part 3, we examine some of the potential ramifications if a business was to wrongly categorise someone as an intern, when they are in fact an employee.

Part 2 of this series, we outline some guidelines for setting up an unpaid intern arrangement that aims to mitigate the risks that can arise when engaging an unpaid intern. In Part 3, we examine some of the potential ramifications if a business was to wrongly categorise someone as an intern, when they are in fact an employee.

1 FWO Media Release ‘Fashion start-up penalised over unpaid internship’, 1 March 2019.