A question is often asked of us about the different ways to structure a company’s share capital. Below is a summary of the Australian legal position and practice with respect to the share capital of an Australian company. It focuses on private companies (ie. companies not listed on ASX).

Introduction to shares

Section 114 of the Corporations Act states that a company must have at least one member. Membership in a company limited by shares (as opposed to a company limited by guarantee) is conveyed upon the holder of a share or shares. That means that a company limited by shares must have at least one shareholder.

While a share may be tangible, in the sense that it may be represented by a physical or electronic certificate, it is also appropriate to view a share as a thing to which a bundle of intangible rights and restrictions of the shareholder are “attached” in respect of the company and its other shareholders.

What determines the bundle of rights and restrictions

A company is broadly empowered by section 254B of the Corporations Act to determine the terms on which shares are issued and the rights and restrictions attaching to them. These can be set out in a range of sources, including:

- the Corporations Act;

- the terms of the agreement under which the shares are issued to a holder;

- the terms of issue of the other shares in the company and the rights and restrictions attached to them (including those which are issued after the shares in question); and

- the rules governing the company (i.e., the Replaceable Rules in the Corporations Act, constitution and/or shareholders agreement),

each of which can determine how the shares in the company operate with respect to the company and each other.

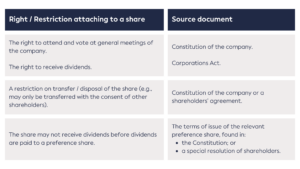

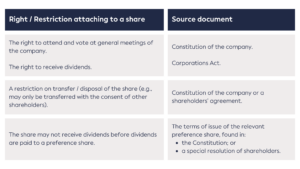

An example is set out in the table below.

Ordinary Shares

Companies have a great deal of flexibility when it comes to how they structure and issue share capital. This is reflected in the Corporations Act, which sets no limits with respect to the share structure of a company (other than section 254A(3) of the Corporations Act, which stipulates that redeemable shares are preference shares, discussed further below).

Usually, a company’s main class of shares is referred to as ‘ordinary shares’. The Corporations Act does not provide a definition for an ordinary share. Ordinary shares are generally considered the least burdensome form of capital instrument that may be issued by a company (and conversely highest risk form of instrument to a holder) – as they do not have any right to repayment or redemption by the company, nor any right to specified dividends or distributions. On a liquidation they rank last in terms of a return of capital to holders of capital instruments, but on the other hand may participate in any surplus remaining once preferred forms of capital instruments have been repaid.

Typically, the constitution of a company will provide ordinary shareholders with the right to:

- receive dividends as declared by the company;

- participate in a return of surplus capital, either in the ordinary course of the business of the company or upon winding-up (liquidation) of the company; and

- receive notice of, attend, and vote at general meetings of the company (typically with one vote per share).

Either the constitution or a shareholder’s agreement may also provide for:

- all shareholders to have a pre-emptive right, in the event that the company seeks to issue more shares, to subscribe for more shares in proportion to their existing shareholding; and

- rights of shareholders to appoint a director.

The Replaceable Rules set out in the Corporations Act, if applicable to a company, operate to grant similar rights to shareholders, however those rules do not specifically apply to ‘ordinary’ shares, but just shares.

On the question of whether a company needs to issue ordinary shares before issuing any other form of share, the High Court of Australia in Beck v Weinstock (2013) 251 CLR 425:

- confirmed earlier authorities, which had held that in order for a so-called preference share to be, in fact, a preference share (including a redeemable preference share) the share must have a right in preference to, or priority over, another ordinary share (which could be any right, not just a preferential right to a dividend or to a return of capital); and

- established that the preferential right attached to a preference share need only be preferential in theory.

The second point arose because the dispute in the case occurred in circumstances where:

- the articles of the company envisioned a number of share classes, including ordinary shares, however at the time in question only shares in four preference classes had been issued (including redeemable shares); and

- the company, controlled by Weinstock, redeemed the shares held by Beck which were worth approximately $7m.

Beck argued that because the company only purported to have preference shares on issue, the redeemable preference shares did not have a real preferential right (as there was no existing ordinary shares over which they were preferred), could not be genuine preference shares and therefore their redemption could not occur by reason of section 254A(3) of the Corporations Act (this section requires that only preference shares may be issued on terms that they are redeemable).

The High Court found for Weinstock and ruled that, provided a preference share was issued on terms which gave it a preferential right over ordinary shares, it was still a preference share despite no ordinary shares ever being issued.

This suggests that a company need not have ordinary share capital on issue, despite some of the possible unusual situations that could arise, such as no shareholder being able to vote in a general meeting of the company (since preference shares are usually non-voting).

The High Court suggested these absurdities could, and would, be avoided by a board ensuring that if necessary ordinary shares be issued, so that a general meeting could proceed. However, a company cannot compel someone to subscribe for ordinary shares, so it may not be in the directors’ control to ensure this occurs.

Despite this High Court authority, we do not recommend companies follow this approach of not having any ordinary share capital on issue.

Preference Shares

Unlike other forms of shares, the Corporations Act and the courts have set some requirements for rights attaching to a class of shares if they are to be considered preference shares, being:

- a requirement for a share to have a genuine preferential right over another class of share; and

- under s254A(1) of the Corporations Act, a requirement for certain preferential rights (such as a priority right to vote, the repayment of capital or to participate in surplus assets or profits) to be set out in the constitution of the company or approved by a special resolution of shareholders.

Provided that the above mentioned requirements are satisfied, the kinds of rights (and restrictions) which can be attached to preference shares are theoretically limitless but tend to fall into several common categories:

- a priority right to receive dividends, the amount of which is often fixed by reference to a fixed percentage return based on their issue price (such as 5% per annum);

- a right to receive dividends either non-cumulatively or cumulatively (cumulative meaning that the holder is entitled to receive, before any dividends are paid on ordinary shares, the aggregate amount of any dividends in previous periods to which the preference shareholder was entitled but which were not paid);

- a priority right to participate in a return of the assets of the company in the event the company goes into liquidation, or in the proceeds of a sale in the event that the company undergoes a trade sale or initial public offering (often called a Liquidation Preference Share); or

- no right to vote at a general meeting, except in certain circumstances (such as when dividends are in arrears for longer than a specified period, or in relation to a matter which affects the rights attached to the preference shares).

The way in which preference shares often have a right to a fixed dividend and/or a return of capital upon liquidation mirrors the rights commonly attributed to types of debt, and in fact preference shares are regarded as a type of “hybrid” financial instrument, in that they have characteristics of both, and are therefore a hybrid of, debt and equity.

Liquidation Preference Shares are commonly used by private equity investors to limit downside risk and increase the certainty of their expected returns. Liquidation Preference Shares may also:

- be participating or non-participating: which respectively means that they entitle their holder to both receive a return of their capital and pro-rata right to participate in distributions of capital, or only to receive back their initial capital;

- have a 1x, 2x, or some other multiple of liquidation preference: which means that they entitle their holder to receive a return of capital which (other than a 1x preference) is greater than their initial capital contribution.

Preference shares may also be:

- redeemable: at the election of either the shareholder (providing downside protection by allowing the holder to trigger a return of capital) or the company (which allows the company to “retire” the preference share when it has the capital to do so, such as in the case of a preference share with a fixed dividend right); or

- convertible: convertible to some other class of share (typically ordinary), at the election of either the company or the holder.

In considering the issue of preference shares, it is important to ensure that their rights are clearly documented, not only to ensure compliance with section 254A of the Corporations Act, but because:

- in the absence of clearly documented rights preference shares are presumed to carry a right to cumulative dividends;

- if a share is given a preference as to payment of dividends ahead of other shares, it is presumed that it carries no right to share in profits available for distribution after the preferential dividend has been paid; and

- if the Replaceable Rules have not been displaced in respect of a company, under the Replaceable Rule in section 250E of the Corporations Act, a preference shareholder will have the same voting rights as an ordinary shareholder.

Founder shares

Still relatively uncommon in the Australian corporate environment, these shares are used more often in the United States and may:

- provide their holders with a right to cast a greater proportion of votes than the number of shares (so-called “super voting” rights);

- “vest” (i.e., are issued to the shareholder) according to a specified schedule (such as 25% per year); and

- carry restrictions on disposal.

Founder shares may also be “deferred” which means that they only entitle their holders to receive a dividend after a specified minimum has been paid to ordinary shareholders.

Within the private context it is difficult to say with certainty why founder shares have not been more widely adopted in Australia, however voting power will often be managed with the distribution of voting (i.e., ordinary) shares and non-voting classes of shares. In the listed environment the position is clearer cut, with the ASX taking a negative view on the inclusion of any “super” voting shares in the capital structure of a listed entity.

Share classes and possible complications

In establishing a share capital structure, companies should also be aware of the provisions in the Corporations Act which apply to:

- share classes; and

- the variation or cancellation of rights attaching to shares in a particular class.

Under section 246B of the Corporations Act:

- if the constitution has a procedure for varying the rights attached to a class of shares, that procedure must be complied with (and the procedure itself cannot be varied or cancelled without complying with the procedure); and

- if there is no procedure in the constitution, then rights attaching to a class of shares can only be varied or cancelled by special resolution passed at a meeting of shareholders in that class (or by written consent of shareholders holding at least 75% of the votes in that class).

Under section 246C of the Corporations Act:

- deemed variation of rights: the issue of shares with different rights to existing shares, where the terms of the new shares are not specified in the constitution or in a document which is lodged with ASIC is deemed to vary the rights attaching to the existing shares;

- deemed variation of rights and creation of new class: where the rights attaching to some shares in a class are varied or cancelled, that is deemed to be a variation to all of the other (non-varied) shares in that class and members who hold shares with the same rights after the variation are deemed to form a separate class; and

- deemed variation of rights attaching to preference shares: unless the terms of the preference shares on issue specifically allow for subsequent issues of preference shares, subsequent issues of preference shares that rank equally with the existing preference shares is deemed to vary the rights of the existing preference shares.

Under section 246D of the Corporations Act, unless all holders of shares in a class consent to the variation or cancellation of their rights, shareholders holding at least 10% of the votes in the class may apply to the court to have the variation set aside. This also applies where the constitution is varied to permit a variation or cancellation of rights attaching to shares in a class if the resolution to vary the constitution is not unanimous.

A multi-class share structure, whether implemented intentionally or unintentionally, can have implications for the company as it may impact the governance and administration requirements of the company by:

- making it more difficult, complex and expensive to value certain shares or the company as a whole; and

- requiring the company to navigate provisions in the Corporations Act or its constitution which specify a process for varying the rights attaching to a particular class of shares.

Given the risk of inadvertently creating a new class of shares or performing an action amounting to a variation of class rights, we recommend that any company looking to issue shares or altering the rights attaching to shares first seek legal advice.

Takeaways

If considering implementing or changing a corporate structure by way of the issue of shares, directors should remember that:

- companies have a great deal of flexibility in structuring their equity capital and issuing shares, however the rights and restrictions attaching to shares should be clearly documented (to avoid possible disputes, but also to prevent the Corporations Act providing holders of ordinary and preference shares with any rights which are not intended);

- companies may not need to implement multi-class share structures in order to achieve commercial or governance objectives, as the ability for a holder to “enjoy” (or be subject to) the bundle of rights (and restrictions) attaching to shares can be specified to change over time, or be based on the identity of the holder of the shares, without creating new classes of shares (such as differential dividend rights); and

- a subsequent issue of shares may have the effect of altering the rights attached to shares which are already on issue (which can trigger statutory protections in the Corporations Act in relation to class rights).