Andrew Lacey

Managing Principal

Unpaid internships are often considered a rite of passage for those entering the workforce. But any business looking to engage an intern must ensure that it does so in accordance with the law. This three-part article series explains the relevant law (Part 1), outlines how to set up a proper intern arrangement (Part 2) and highlights the importance of getting the arrangement right (Part 3).

In this article, Part 2 in this series on internships, we outline the clauses that you should include in an internship agreement to protect your business from the risks associated with engaging an intern.

When a business decides to engage an unpaid intern it needs to take the time to set up the internship arrangement properly. As outlined in Part 1 of this series, a true unpaid intern is not entitled to receive remuneration or other employment benefits. For this reason, businesses often overlook the importance of entering into an internship agreement to mitigate the risks associated with engaging an intern.

Where an employment relationship exists, businesses have certain automatic legal protections. Examples of these are the duties on an employee not to disclose confidential information, follow lawful and reasonable directions and use skill and care in the performance of their work. In the absence of an employment relationship, a business doesn’t receive these protections as a matter of course – the intern must agree to them. An internship agreement facilitates this.

Additionally, businesses need to remember that duties are also owed to interns. Work health and safety obligations are an example of this. A proper intern agreement will assist a business and its management to meet these obligations.

An intern agreement should always be entered into before the internship begins. Like an employment contract or contractor agreement, an intern agreement acts to clarify the parties’ expectations and, in particular, the duties and obligations of the intern. It also contains certain protections for the business.

To ensure that both the business and intern are clear about the terms of the internship, the intern agreement should set out the following matters:

Because an employment or contracting relationship does not exist, the business is not required by law to provide the intern with notice of the termination of the internship. To provide the most flexibility, we recommend that either party be permitted to terminate the internship with immediate effect at any time.

As mentioned above, engaging an intern does not give a business the automatic protections that an employment relationship does. For this reason, duties and responsibilities should be imposed on the intern through a written intern agreement.

Some of the broad duties and responsibilities that businesses may look to impose on an intern include a need to:

There are many other duties and responsibilities that a business might consider including in the internship agreement, depending on the nature of its operations and the type of work the intern will be exposed to or assist with.

In most cases, interns will be exposed to information that is confidential to the business and its operations. While the level of disclosure will depend on the work observed or performed by the intern, it is good practice to require an intern to agree not to disclose any confidential information they come to know as a result of the internship.

The internship agreement should define what constitutes “confidential information”. Although consideration should be given to the nature of the business and the areas to which the intern may be exposed, “confidential information” can include client lists, pricing strategies, internal processes, and business, sales and marketing plans.

Unlike employees, the ownership of any intellectual property created by an intern in the course of performing their internship may not automatically vest in the business. For this reason, it is important to ensure that the intern agrees to assign to the business all rights, title and interests in any intellectual property created by them during the course of the internship.

Another option is to permit the intern to retain ownership of any intellectual property they create, but have the intern provide the business with a licence to use the intellectual property as it wishes. Whether the licence will entitle the intern to receive royalties from the business should be set out in the intern agreement.

Example: Ownership of computer code written by intern

Having just finished her degree in computer science, Hannah starts an internship with a software development business to get some industry experience. During the internship, Hannah writes a code that the business would like to use in one of the programs it is developing. Because Hannah isn’t an employee of the business, she automatically owns the code she has written and the business cannot use it without her permission.

If the business wants to own the code, Hannah needs to assign the ownership of the code to the business.

If the business is happy for Hannah to retain ownership of the code, but wants permission to continue to use it in the software, Hannah needs to provide the business with a licence to use the code. Depending on the agreement, the licence may or may not entitle Hannah to receive royalties.

Even if the intern does not retain ownership in any intellectual property they create as part of the internship, they will still have the three following “moral rights” in relation to any copyright works:

While an intern’s moral rights cannot be transferred, assigned or sold to the business, the intern can consent to the business using the intern’s works as they wish.

Example: Use of blog post written by intern

Phillip decides to commence an unpaid internship at a small accounting firm while he is studying a business administration course. At the end of the internship, Phillip writes a short blog post on his experience as an intern. The accounting firm decides it would like to use it on their website and in marketing material.

Unless Phillip has consented to the accounting firm infringing his moral rights, it is not permitted to publish any part of Phillip’s blog post unless it clearly and prominently identifies him as the author of the material. The accounting firm is also not permitted to edit Phillip’s blog post in a way that might prejudice Phillip’s reputation, such as by making fun of him.

Businesses, and certain individuals within a business, have a duty to ensure the health and safety of workers and visitors, including interns. Accordingly, businesses must do everything reasonably practicable to ensure the physical and mental wellbeing of interns in their workplace. It is imperative that interns be required to follow health and safety procedures to ensure that they do not put the health and safety of other workers at risk. Significant penalties (including fines and imprisonment) can be imposed for breaches of work health and safety laws.

To assist a business meet its work health and safety obligations, the internship agreement should require the intern to follow all relevant health and safety policies and procedures, and report any health and safety risks, or incidents, to their manager or supervisor.

In addition, the intern should also be required to undertake induction training about the work health and safety policies and procedures of the business.

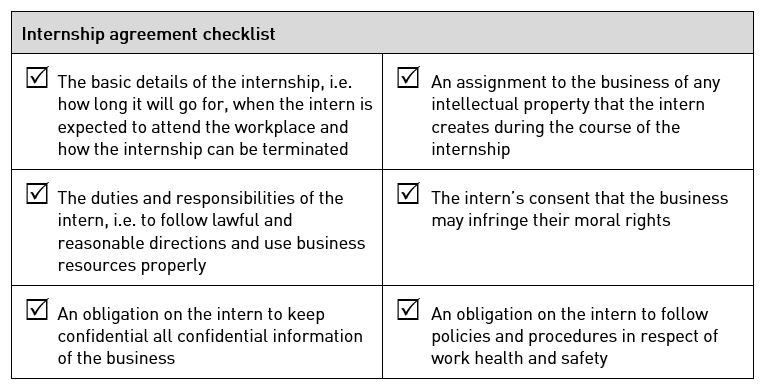

Whilst the terms to be included in an intern agreement should be considered in the context of the specific internship, we set out below a checklist of the provisions that we would recommend be included in all intern agreements.

Part 3 of our series looks at some real examples that highlight the importance of correctly categorising an unpaid internship and ensuring that the internship is set up properly.

Part 3 of our series looks at some real examples that highlight the importance of correctly categorising an unpaid internship and ensuring that the internship is set up properly.